...uplinks, including horizontal links to competitors or antipatterns

- Sibling: Goal Factoring

- Up might be something like motivation engineering

Sometimes we are psychologically averse to doing things that are actually good for us to do.

There are many activities we might engage in and enjoy but for an aversion that prevents us from engaging in that activity.

The key insight behind aversion factoring is that no activity simply is aversive, at its core. There’s no fundamental quantity called “running” that “just sucks,” for instance—running is a complex system of experiences, and summing or averaging across all of them causes us to lose valuable detail. By factoring "running" into component experiences, we can evaluate each experience separately, and we may find that we’re more or less okay with all of them, and that the ones that are the most negative can be addressed individually.

For example, we might factor "running" into the following components:

- Wearing running shoes and athletic clothes (verdict: seems fine)

- Feet slapping against the pavement (verdict: kind of unpleasant?)

- Legs and arms pumping, muscles burning (verdict: no problem)

- Shins and knees aching (verdict: VERY BAD)

- Rapid heart rate and breathing (verdict: not my favorite part of exercising, but it’s also not really a big deal)

- Being outside on sidewalks in the heat (verdict: problematic)

- Sweating until my shirt sticks to me (verdict: who cares?)

- Wind in my face and hair (verdict: great!)

- Feeling fast and light (verdict: AWESOME)

- Other people looking at me and judging me (verdict: definitely bad)

The purpose of the Aversion Factoring technique is to give you the tools you’ll need to identify and overcome aversions.

Discussion of when the solution is appropriate.

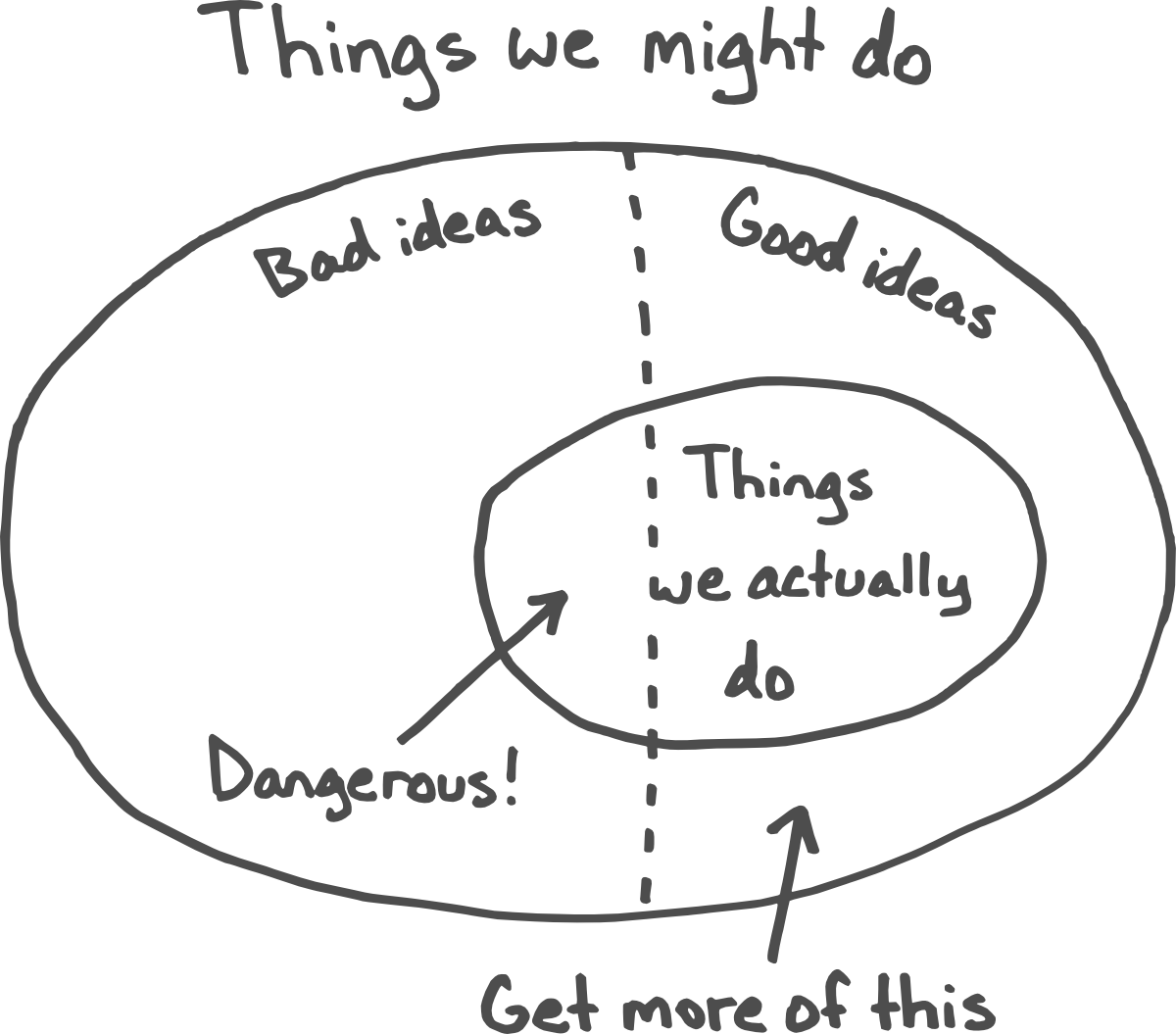

Of course, not every aversion should be overcome—it would probably be counterproductive to lose your aversion to being hit by cars, for example. In the set of [dancing, singing, public speaking, interacting with strangers, asking for help, doing taxes, getting into fights, tinkering with your car, going to parties, trading stocks, feeling comfortable naked, cleaning up your apartment, learning martial arts, calling old friends, firing guns, writing code, & going on more dates], there are probably some things you’re averse to and would benefit from doing more of, but there are also probably some things you’re averse to and have no real need to do, or actively and correctly avoid.

Both [a policy of immediately trusting your aversions] and [a policy of immediately dismissing or disregarding your aversions] are dumb. Aversions are a trigger to look closer. The goal is to have the affordance to overcome aversions, so that when you recognize one in yourself, it’s up to you whether or not to do something about it (as opposed to being outside of your control).

The Aversion Factoring algorithm

1. Choose an activity

- Something you don’t already do, or do but find unpleasant

- Something that is plausibly good or worth doing

2. Check your motivation

- Search for positive attributes or consequences of the activity (sometimes called yum factors). Make sure that you know exactly what about the activity is emotionally appealing or valuable.

- Consider goal factoring—could there be more efficient ways of achieving the yum factors than the chosen activity?

- Consider internal double crux, described in a later section of this sequence—if the activity is a good way to achieve your goals, but your System 1 doesn’t give you a visceral sense of progress while you do it, you may want to reflect on the causal link or try to strengthen the emotional connection.

3. Factor the aversion out into parts

- Don’t restrict your search to “reasonable” impulses. If the feeling you have is “I’m not allowed to change my car’s oil,” then write it down and give yourself permission to think about it explicitly.

- Include trivial inconveniences (e.g. you don’t floss because the floss is in a drawer that you never open).

- Be as specific as possible. Often, simple phrases like “it’s boring” or “it’s hard” are masks for relevant detail (e.g. “I feel indignant about having to do paperwork” or “I don’t like setting aside enough time to get it done, because then I’ll be locked into doing it for a large block of time.”

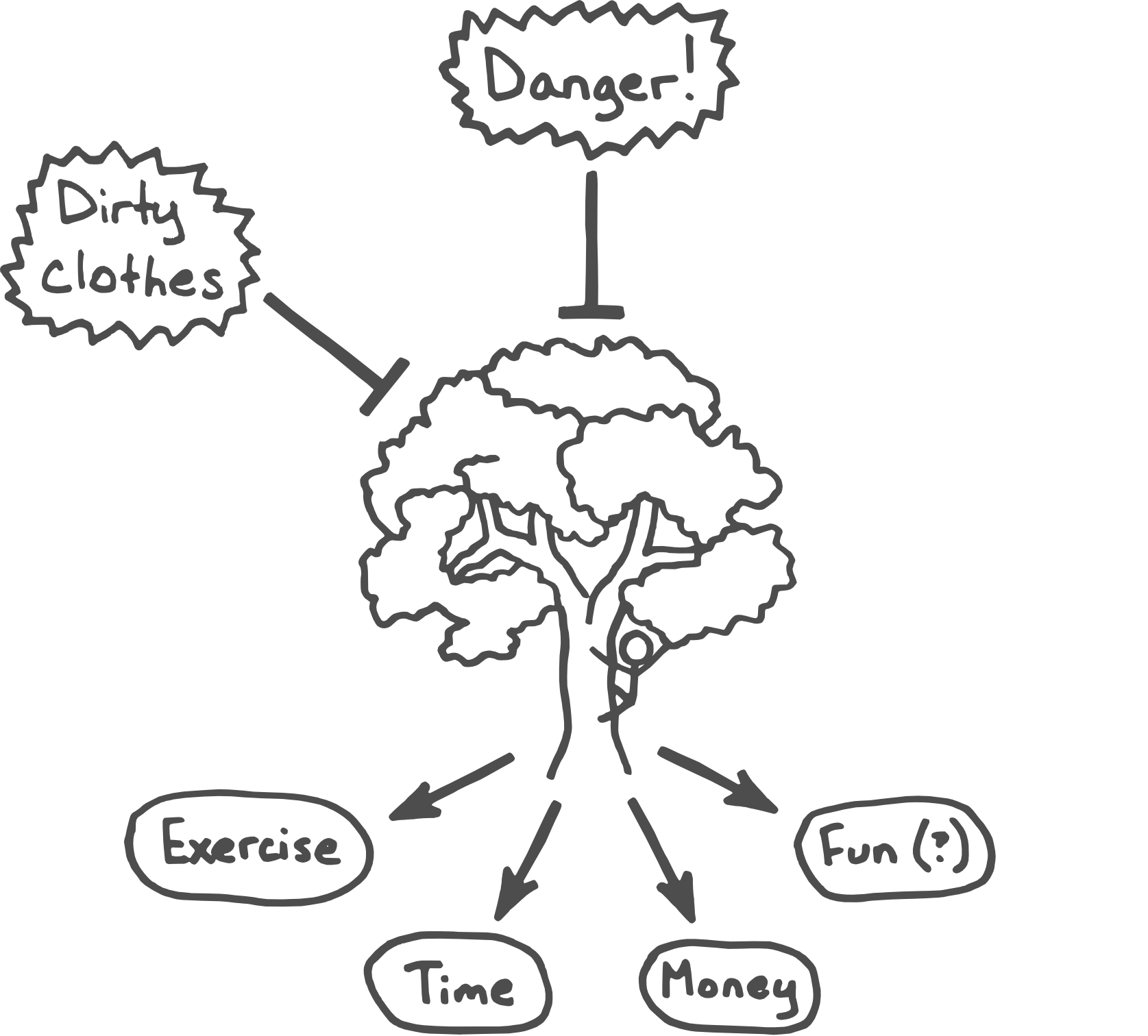

4. Draw a causal graph

- Include activities, steps, goals, yum factors, aversions, and any- thing else that feels relevant to the situation. Use thought bubbles, boxes, balloons, arrows, and dotted lines—anything that helps you capture the specifics of how the various parts interrelate.

- Check for completeness (e.g. with mindful walkthroughs or button tests). Update the graph as new things come to mind.

5. Implement possible solutions

- Address external factors with concrete action ("plots and schemes"), as when Critch changed his climbing style and purchased dark jeans.

- Address internal factors with recalibration techniques such as exposure therapy and big-picture reframing.

Therefore:

Factor aversive activities into component experiences in order to see if there are ways to actually engage in activities that would be good for you.

downlinks